FreeCon Founders

American greatness rests on a foundation of timeless wisdom

On July 5, 1926, President Calvin Coolidge gave a speech in Philadelphia commemorating the 150th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. His address remains among the most powerful defenses of the American Founding ever presented.

“If all men are created equal, that is final,” Coolidge said. “If they are endowed with inalienable rights, that is final. If governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed, that is final. No advance, no progress can be made beyond these propositions.

“If anyone wishes to deny their truth or their soundness, the only direction in which he can proceed historically is not forward, but backward toward the time when there was no equality, no rights of the individual, no rule of the people.

“Those who wish to proceed in that direction can not lay claim to progress. They are reactionary. Their ideas are not more modern, but more ancient, than those of the Revolutionary fathers.”

Freedom Conservatives couldn’t agree more. Our Statement of Principles calls the federal constitution “the best arrangement yet devised for granting government the just authority to fulfill its proper role, while restraining it from the concentration and abuse of power.”

Here are three FreeCons who insist the Right cannot offer a compelling and achievable vision of America’s future by abandoning America’s founding principles.

What is it for?

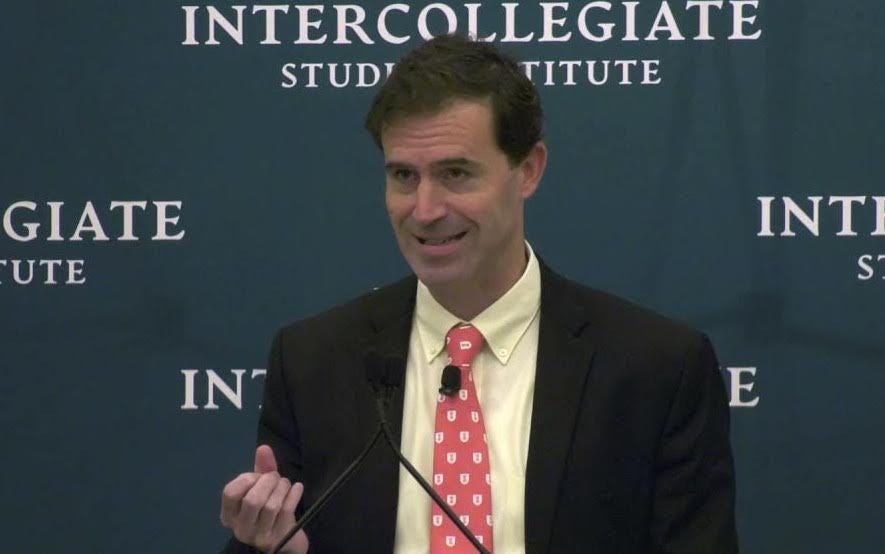

Richard Reinsch is editor-in-chief and director of publications at the American Institute for Economic Research. He is also a senior writer at Law & Liberty, a journal he founded and for which he served as editor for 10 years.

The former director of the Heritage Foundation’s B. Kenneth Simon Center for American Studies, Reinsch is coauthor with Peter A. Lawler of A Constitution in Full: Recovering the Unwritten Foundation of American Liberty.

In a recent Acton Institute review of Up from Conservatism — a collection of essays by National Conservatives and other leaders of the populist Right — Reinsch, a FreeCon signatory, took them to task for abandoning and denigrating the country’s governing traditions.

One essayist, for example, argues that “much of modern American conservatism has been based on foolish and self-defeating appeals to the Founders.”

This book “omits the word conservatism except when it is being insulted,” Reinsch wrote, “and rarely ties its aims explicitly to the recovery of our constitutional order.” In reality, “our country is inherently defined and articulated by a written Constitution built on an essential idea for limiting and channeling power through self-government.”

By contrast, NatCons and their allies offer “fierceness and ruthless action in the political realm” without spelling out “what it is all for.”

Least drastic cures best

Jay Cost is the Gerald R. Ford nonresident senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, where he focuses on political theory, Congress, and elections. He is also a visiting scholar at Grove City College and a FreeCon signatory.

In a piece for The Dispatch, Cost discussed proposals to reform Congress and the Electoral College. While many voters say they’re dissatisfied with their political system, he wrote, that doesn’t necessarily mean they’ll support sweeping changes by constitutional amendment — a process that is difficult by design.

Fortunately, Cost wrote, “many aspects of our system could be transformed without touching the Constitution. And as we consider what ails our body politic, it makes sense to prioritize the least drastic ways to cure it.”

For example, it would only take a statute to expanding the size of the U.S. House. That would make the body more representative while reducing power imbalances within the Electoral College.

States can also award some of their electors by congressional district, as Maine and Nebraska do, rather than holding winner-take-all votes for president.

As for progressive calls change the composition of the U.S. Senate, Cost is unpersuaded. “To hold a large country like ours together, we must make sure every place feels included. The Senate helps us accomplish that task.”

Liberty of mind

A professor of politics at Ave Maria University, John Colman also directs the university’s honors program. His latest book is Everyone Orthodox to Themselves: John Locke and His American Students on Religion and Liberal Society.

In an essay for FUSION, Colman compared the language of the Freedom Conservatism Statement of Principles — which he signed — with that of previous statements, including last year’s declaration of National Conservatism.

While some have criticized the FreeCon statement for making no explicit reference to God, Colman argued that it “represents an important current of thinking, dating back to the Founding, that understands the danger that imposed religious orthodoxy presents to religious liberty.”

Founders such as George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and James Madison certainly believed that “religion and the Bible” were “an important source of the virtues necessary to maintain our experiment in self-government,” he wrote.

But they also worried that attempts to enshrine specific passages or interpretation of scripture in government doctrine would be “fraught with risk,” requiring politicians to take sides on matters best left to civil society.

“Freedom Conservatism’s understanding of freedom of conscience as the right to ‘say and think what one believes to be true,’” Colman concluded, “is a stand-in defense of what Madison call the most ‘sacred of all property’ we possess — the free use of our mind, the choice of objects upon which to employ it, in our opinions, and the free communication of them.”

Other coverage

On his Press Club C podcast, signatory Ray Keating interviewed one of the leaders of the FreeCon project, John Hood, who explained the statement’s “Full Faith and Credit” language about fiscal responsibility this way: “The federal government needs to re-earn the faith of the public by restoring its credit.”

In the Freemen News-Letter, editor and FreeCon signatory Justin Stapely reacted to last week’s congressional testimony by the leaders of three elite universities. “We are living in a time when the full administrative authority and power of a public university are brought to bear against ‘microaggressions,’” he wrote, “but calls for ‘the intentional destruction of a people in whole or in part’ are essentially shrugged at and considered non-problematic until it, apparently, culminates in actual violence against Jews.”